RI Coastal Resources Management Council

...to preserve, protect, develop, and restore coastal resources for all Rhode Islanders

...to preserve, protect, develop, and restore coastal resources for all Rhode Islanders

Coastweeks 2017 Ninigret marsh tour: Salt marsh 101 with CRMC

While it might not be possible to save all of the remaining salt marshes in Rhode Island – an estimated 4,000 acres – the R.I. Coastal Resources Management Council (CRMC) is hoping to buy them a bit more time in the face of accelerating sea level rise.

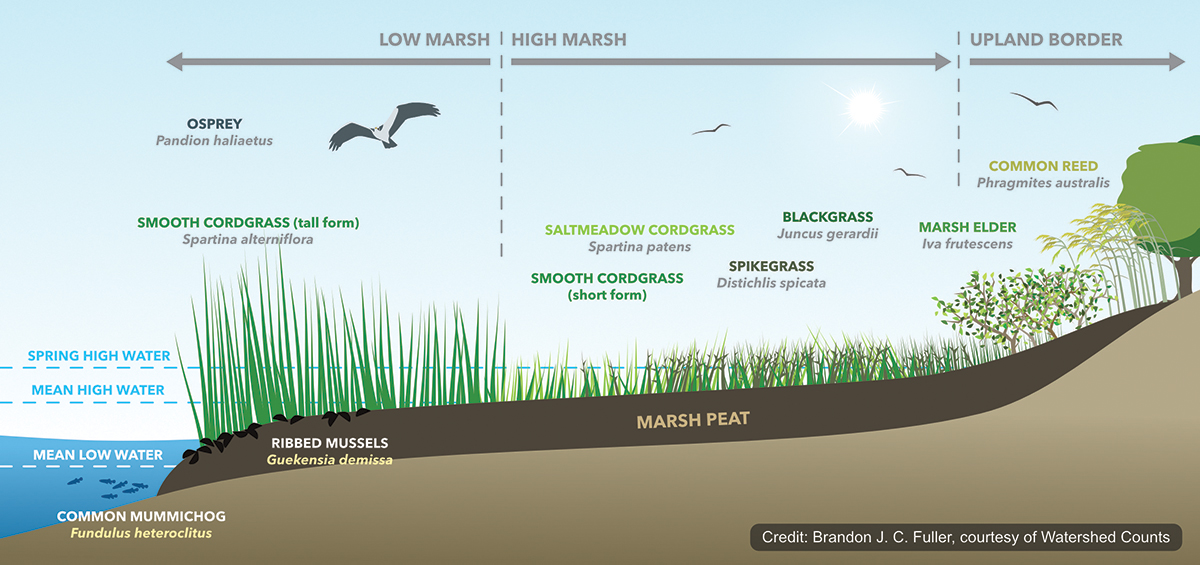

“Tidal inundation is what drives the composition of marsh plant communities,” said Caitlin Chaffee, CRMC’s coastal policy analyst and salt marsh specialist one warm September morning as she spoke to a group of Coastweeks 2017 participants on Ninigret salt marsh in Charlestown. The marsh was the site of a recent CRMC-led restoration and elevation enhancement project designed to make it more resilient to climate change impacts. “They’re very dynamic systems – essentially they build up over time. The tide brings in sediment and organic matter accumulates on the marsh surface.”

As part of the annual Coastweeks celebration, a month-long series of events geared toward getting Rhode Islanders outside to learn about and celebrate the coast and sponsored by the CRMC and Rhode Island Sea Grant, Chaffee and Save The Bay staff led two walking tours on the Ninigret marsh to show the restoration work and planting, and to also show parts of the marsh that remain distressed.

“Sea levels have been rising steadily over time, but now we’re seeing an acceleration of that process,” Chaffee said. “Marshes have historically kept up with sea level rise, but now it’s outpacing accretion and we’re seeing areas of the marsh die-off.”

It is estimated that Rhode Island has lost 53 percent of its marshes to filling and development in the last 200-plus years. Salt marshes are among the most productive habitats on the planet, supporting economic and environmental benefits: they serve as nursery and forage habitat for marine fish and invertebrates, as well as nesting and migratory feeding sites for a number of bird species. Salt marshes improve water quality by filtering pollutants and sequestering nitrogen from nearby upland sources. They also help reduce the damage from coastal storms and erosion to shoreline infrastructure by absorbing wave energy.

As of 2010, coastal wetlands in Rhode Island comprised about 4,000 acres in and along Narragansett Bay and the coastal lagoons of the southern coastline, according to the 2015 Rhode Island Sea Level Affecting Marshes Model (SLAMM) Project Summary Report.

“As part of a research project on salt marsh losses in New England, Bromberg and Bertness (2005) calculated that Rhode Island lost approximately 1,831 hectares (4,524 acres) or 53 percent of salt marshes over the previous 200 years based on a study of historical maps,” the report states.

In 2016, the CRMC and its project partners restored and conducted elevation enhancement in approximate 25 acres of the Ninigret salt marsh. The goal of the pilot project was to increase the elevation of the marsh where vegetation had died from increased flooding due to sea level rise. It included using dredged material from the Charlestown Breachway – pumped directly onto the marsh – and replanting native Ninigret salt marsh plants the following spring.

“With thin-layer deposition, we actually add sediment to the marsh surface, which if you know the history of salt marsh restoration, seems like a very foreign idea,” Chaffee said. “The goal is to buy [the marsh] some time.”

The three sea level rise scenarios utilized in the SLAMM maps depict changes in salt marsh under a 1, 3 and 5-foot sea level rise, and show in the near and long-term time frames, Rhode Island faces substantial losses of coastal wetlands and some freshwater wetlands near the coast. Total statewide losses of existing coastal wetlands are projected, according to the SLAMM report, at 13 percent, 52 percent, and 87 percent under the 1, 3, and 5-foot scenarios, respectively, if there is no planning to allow for these wetlands to migrate inland naturally, with no manmade obstruction.

Salt Marsh 101: an illustration showing a cross-section of a healthy salt marsh

Above, left, the degraded salt marsh prior to restoration. At right, a view of Ninigret post-restoration in 2017 with some natural re-seeding and plantings