RI Coastal Resources Management Council

...to preserve, protect, develop, and restore coastal resources for all Rhode Islanders

...to preserve, protect, develop, and restore coastal resources for all Rhode Islanders

Presented by the Rhode Island Coastal Resources Management Council and RI Sea Grant, “Shoreline Access for All: Environmental Justice along the Coast” was the second webinar in a summer series of programming regarding shoreline public access across the state. Kate Mulvaney, a social scientist for the US Environmental Protection Agency, introduced environmental justice in the coastal access context and discussed findings from a study investigating relative access to coastal public access points based on race, income, and geographical location in Rhode Island. Julia Twichell, watershed and GIS specialist for the Narragansett Bay Estuary Program (NBEP), presented research conducted in collaboration with the EPA, that used anonymous cell phone data to track visits to coastal public access points around Narragansett Bay and discussed opportunities to improve coastal access based on the results of the study. Finally, Leah Feldman, coastal policy analyst for the CRMC, presented research she conducted on coastal zone access and an experiential education program in Newport, RI, as well as connections to CRMC’s current work to improve equitable shoreline access.

Kate Mulvaney: Inequities in Coastal Access

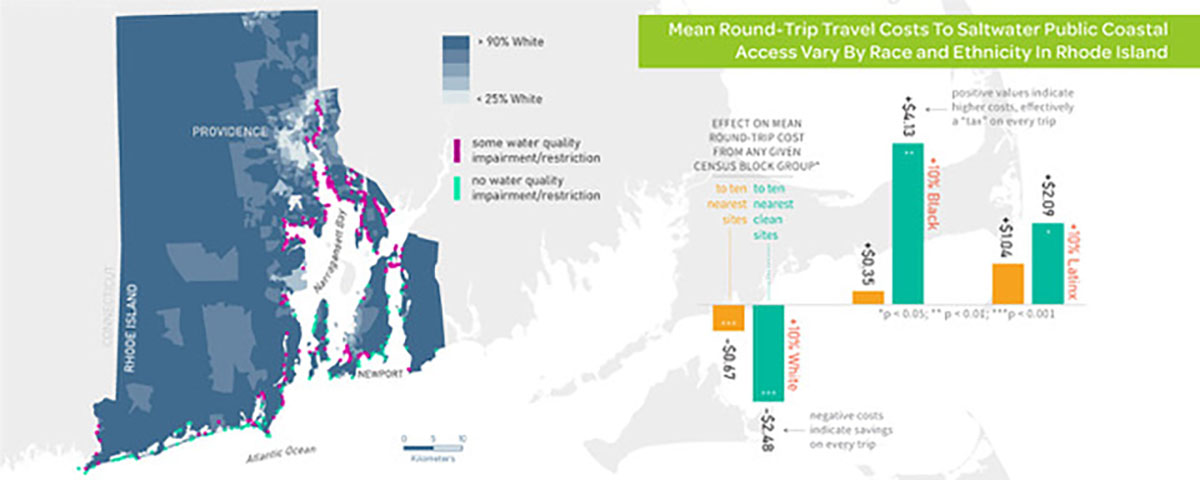

Mean round-trip travel costs to public coastal access points in Rhode Island. Image courtesy of Narragansett Bay Estuary Program.

Environmental justice (EJ) is the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income with respect to the development, implementation and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations and policies (US EPA, 2021). The study focused on distributional justice, or the concept that benefits and burdens of environmental resources are distributed fairly among all people, regardless of gender, age, nationality, sexual orientation, social class, race, ethnicity or other factors. There are often barriers that can impact coastal accessibility, from transportation availability to water quality.

This research, conducted by the EPA in collaboration with staff from the Coastal Institute at the University of Rhode Island, the Narragansett Bay Estuary Program, and others, aimed to determine whether different demographic groups have equitable opportunities to access and recreate on the Rhode Island coastline. To answer this question, they used equity mapping methods, which breaks up census block groups into smaller clusters with roughly the same number of people, and examined the distance from each cluster to the ten nearest beaches or shoreline public access points, along with the distance to the ten nearest coastal access points or beaches without a history of water quality impairment. Then, to identify factors that may change the distance to these access points, the researchers looked at the characteristics of each census block group, including race and ethnicity, income, home value, unemployment, the percentage of seasonal housing in the census block group, vehicle ownership, how urbanized an area is, the density of the population, and location. According to recent Census data, 74% of Rhode Island’s population identify as non-Latinx White. The highest proportion of Black and Latinx populations live in urbanized areas surrounding Providence, while the highest proportion of Asian populations reside in suburban areas around Providence, and the highest proportion of Indigenous Americans live near or on the Narragansett tribal lands.

On average, any given census block is roughly six miles from the nearest ten access points, but that distance is less for census block groups that have a higher proportion of people who identify as non-Latinx White, and the average distance is farther if a census block group has a higher proportion population that is Black or Latinx. This trend was also observed when looking at the distance from census groups to coastal access points with no water quality impairments. Beaches were slightly farther for all census groups, with an average distance of 10 miles to any beach and an average distance of 31 miles to the cleanest beach. Again, census groups with higher White populations were closer to beaches and clean beaches than census groups with higher Black and Latinx populations. The results of this study show that there are statewide inequities in coastal access opportunities related to race and ethnicity. One strategy to increase equality of public access is to strategically place coastal access points closer to populations who are historically underserved and to consider addressing barriers to entry including transportation, fees, and permits, as well as to improve the quality of existing proximal access points.

Julia Twichell: How do we use our Coasts?

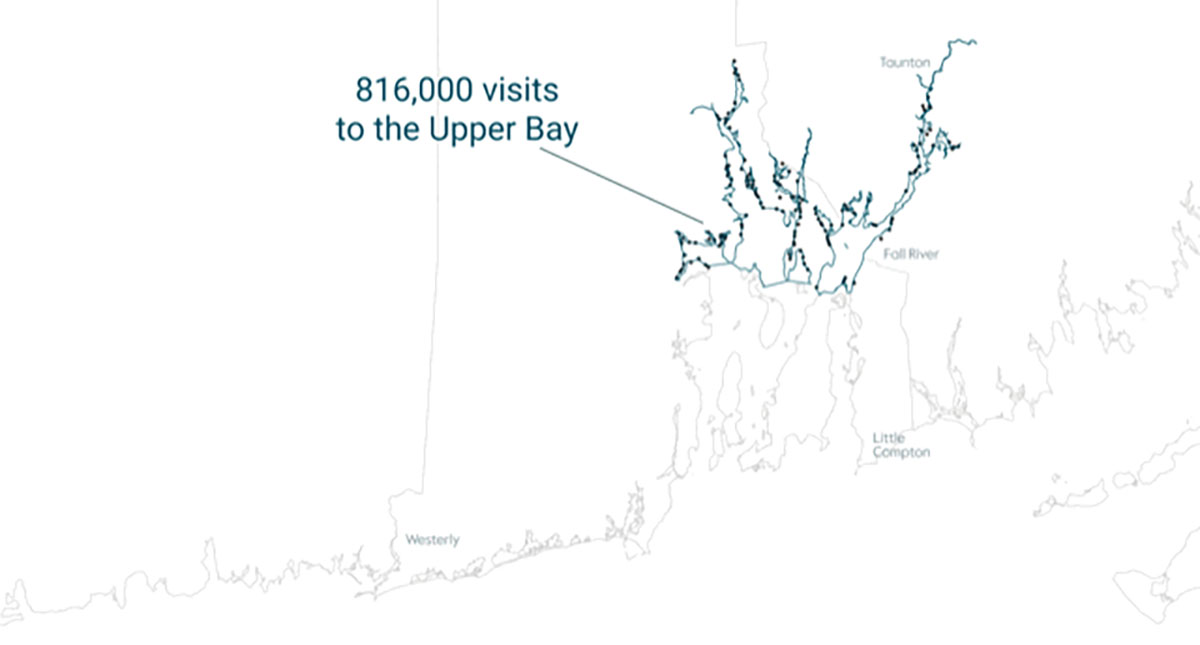

Visits to the Rhode Island coastline in Summer 2019. Image Courtesy of Narragansett Bay Estuary Program.

This study examined visitation to the Rhode Island coastline using over 400 public access points in the region. Researchers from the NBEP and EPA acquired cell phone data from a company called Airsage to document visitation to all of these points and determine where visitation is occurring, and where visitors travel from to visit these coastal locations. The anonymous cell phone data was collected from June to September 2019 to capture peak usage during the summer months. Each coastal site was delineated using satellite imagery, and counts were collected using phone pings occurring within each site between 8 a.m. and 6 p.m. In total, approximately 2.5 million visits to public shoreline access points, from beaches, marinas, and boat ramps to state parks and public right-of-ways, were recorded over the course of the summer. Around 500,000 visits were to beaches, another 500,000 visits were to scenic areas, parks and trails, and one million visits were to marinas, boat ramps, and docks. Roughly 150,000 visits to right-of-ways were recorded across the study area. Each recorded visit also included an associated home location aggregated to a census block group, allowing the researchers to develop a visitor origin map. While the majority of visitors came from around New England, specifically close to the Rhode Island coast, there were visitors from all 50 states in the U.S.

The collected data and generated maps can help researchers to visually understand how people are visiting these different sites, as well as provide data for each site which can be compared with the site characteristics, including water quality, parking, transportation availability, and cost. This information can then be used to determine how to better accommodate use of the site, and how to distribute resources strategically to match actual use of the sites, including conducting monitoring, designating parking areas, trash services, and others.

Julia and her fellow researchers also investigated whether water quality or environmental conditions affected visitation. Regional visitation data was overlaid on maps of environmental factors such as water quality impairments and shellfish harvesting areas to identify relationships between environmental factors and visitation. They found that despite areas of decreased water quality in the upper bay, coastal accesses in the area were still well used, showing that water quality does not necessarily deter visitors from these sites. Restoring environmental quality at existing access points and creating high quality public access points closer to densely populated areas is a possible strategy for enhancing equity in the coastal access space.

For more information on this project, visit How Do We Use Our Coasts, an interactive StoryMap created by the Narragansett Bay Estuary Program.

Leah Feldman: Coastal Access Inequities in Newport, RI

Pell Elementary School students sailing in Newport. Image courtesy of Donna Kelly, Pell Elementary Sail Newport Program.

The Coastal Zone Management Act was passed in 1972, creating a national policy and program for the management, beneficial use, protection and development of the coastal zone, with a focus on addressing that competition between public and private use of the shoreline. However, the Act failed to anticipate the enormous challenges presented by growing populations and limited resources. The Act prevented the coast from being dominated by industry, but didn’t fully protect the coast from being controlled by private interests, specifically of a singular populace. Leah’s research focused on Newport, Rhode Island, at Pell Elementary School, where 33% of students identify as Hispanic or Latino, 28.9% identify as Black or African-American, and 25% of students live below the federal poverty line. Today's Newport is a racially, ethnically, and financially diverse place, with a lower median income than the rest of the state and a significant disparity in wage distribution.

In 2017, Sail Newport and the Pell Elementary school sailing program partnered, allowing the school’s fourth grade students to learn to sail as part of their regular school day. The 16-week program exposed students to life in the waters of the Narragansett Bay and taught sailing, sustainability concepts, marine science, and weather and ocean conservation ideas. The study investigated three key research questions: what impact this program had on the students’ knowledge, attitudes and behaviors regarding Narragansett Bay and various environmental features; what feelings of connectedness to nature and the coastline arose in relation to this program; and what are the potential connections between knowledge attitudes and behaviors regarding coastal recreational practices and beliefs?

To answer these questions, program participants, along with a control group of Pell Elementary students who had not participated in the program, completed surveys. The study revealed that program participants—the students who experienced increased coastal access—showed increases in their sense of belonging to the coast, sense of pro-environmental behavior, and desire to continue being on the water in the future. Students who said that they wanted to be future boaters were more likely to feel like they belong at the coast and were more likely to be participants than non-participants. Students learned to love the sport of sailing, and there was a willingness for participants to return to the coast and to feel a sense of belonging, creating potentially a more equitable and diverse coast.

Though the Rhode Island Constitution guarantees citizens the rights to swim in the sea, gather seaweed, or fish from the shore, getting access to the shore can be difficult, particularly in urban areas with environmental justice concerns. For example, though Providence is one of the most densely populated areas of the state, just three of the 230 CRMC-designated right-of-ways are located in the city. The study results highlighted the importance of bringing people to the water, particularly those who otherwise might not have the opportunity to recreate along the coast, which can be facilitated by enhancing shoreline public access. The Coastal Resources Management Council is dedicated to not only expanding and improving our public access to the shore, but also to working with partners to establish coastal buffers rather than armoring the shoreline, which can provide a lot of co-benefits such as public access, habitat improvement, stabilization of the shore, and filtering runoff into the water. CRMC’s goal is to establish one right-of-way for every mile of shoreline in Rhode Island, equating to over 400 accessible rights-of-way.

Coastal Access and the CRMC

Once a site has been designated as a CRMC right of way, the public's right to pass over that site to access tidal waters of the state is protected forever. The CRMC prohibits any activities that would obstruct the public's use, and pursues legal action against individuals that block or impede public access at designated rights way. Before reaching the CRMC's designation process a detailed review of town records and historical documents is conducted so that the right right-of-way can be properly documented. Cities and towns can assist in this designation process by identifying potential public rights of ways, conducting some of their own background research, and gathering evidence which the CRMC legal staff can then verify and then use during the hearing process. Guidance documents for how the public can assist with this process can be found at www.crmc.ri.gov/publicaccess. Groups or individuals can also support shoreline public access by participating in CRMC’s Adopt-an-Access program, where sponsors can ensure that that particular right-of-way is maintained and protected as a scenic access point to be utilized and enjoyed by the public. It becomes further protected from development and really is a great way to assist in this process. To partner with the CRMC to sponsor a right-of-way, please contact Leah Feldman or Kevin Cute at CRMC.